In this series of articles, I am taking the opportunity each month to look in more depth at individual organisations. How are they seeking to be more sustainable and, importantly, how are they seeking to advise and support members or customers?

This month we focus on two local authorities both fully committed to sustainable practice and in particular look at aspects of their approaches to weed management in urban areas. Lessons learnt and experiences are of course also very relevant to every subsector of amenity and sports surface management.

Local authorities throughout the UK are committed to defined sustainability targets and, in all their operations, to deliver sustainable practice. However the ways in which this is interpreted varies and can create challenge. Direct lobbying often creates demands from council leaders to abandon use of pesticides, particularly in relation to weed control. Yet those at operational level question if such a strategy is truly sustainable or deliverable. In truth, as often stated in these articles, the most sustainable way forward is to adopt a fully integrated approach – making use of all the tools available to produce the required outcome in the most sustainable manner. It is not a question of which particular method is best but which particular mix of methods is best for specific situations.

Following requests to reduce reliance on glyphosate and adopt more sustainable practice, South Lanarkshire Council, decided to embark on a project evaluating its approaches and seek to identify the best practice they should follow. The council is the fifth largest in Scotland covering 1800 square kilometres and has a population of approximately 320,000. In total it has to manage weeds with 5240 kilometres of road channels kerb edges, hard standing of 2 million square centimetres, 2600 properties needing garden care, 1.4 million square metres spot treating beds and almost 2 million metres of grass edges. Quite a task, but typical of authorities across the UK.

USE OF TRIALS

The trials summarised here followed increasing public and councillor concern about the use of pesticides for weed control, particularly those containing glyphosate, and the perceived risks and dangers associated with using these products. In February 2021, officers responded to the council explaining in detail reasons for their use of herbicides, locations of use and the likely impacts on infrastructure if weed growth was not controlled. They also referred to alternatives that had been trialled by colleagues in other Scottish authorities, and their success or otherwise. This led to agreement to pilot a number of different approaches still seeking desired weed control but also providing potential for reducing longer term cost.

At the outset, key reasons for the need to control weeds were identified as follows:

USING A RANGE OF METHODS

The project then trialled a range of control methods normally in combination in an integrated approach including:

The outcomes have demonstrated that the use of glyphosate remains an essential element in weed control but that reduced quantities are possible in adopting a fully integrated and sustainable approach. Indeed comparing 2023 to 2019 years, total glyphosate use has decreased by about a third. This is a significant achievement and testament to the work undertaken to reduce usage, trial alternatives methods and work towards improving and protecting our environment. The trial process has demonstrated a clear direction of travel for decreasing usage of glyphosate and the council and service aim to continue reviewing their use of glyphosate whilst utilising a number of alternative methods.

CASE STUDY IN WALES

Similar pressures to reduce glyphosate use apply across the UK and a second example highlighted in this article refers to the City of Cardiff. Following extensive discussions, in 2021, the Council and its main contractor trialled three principal pavement weed control methods across the City to find out how effective and sustainable each method was, as measured against four key criteria including cost, environmental impact, customer satisfaction and quality. Control methods trialled included glyphosate-based herbicide (applied three times per year), acetic acid-based herbicide (applied four times per year) and hot foam herbicide (applied three times per year). The project was overseen by an independent consultancy who subsequently produced a detail report on the outcome.

The following conclusions were made in the final consultancy report arising from the summary of outcomes as reported. The efficacy and sustainability results showed that glyphosate was the most sustainable, being cost effective, with low environmental impacts and high customer satisfaction and quality. In contrast, acetic acid delivered intermediate costs and environmental impacts with low customer satisfaction and quality, while hot foam generated high costs and environmental impacts, with mixed customer satisfaction and quality. Based on cost, environmental, customer and quality criteria (efficacy and sustainability criteria) measured, the trial indicates that, in this given situation, the most effective and sustainable weed control method currently available for pavement weed control by the council involves the use of glyphosate-based herbicide applied within a fully integrated approach. However it is made clear that every situation will vary and consequently approaches used.

OTHER OUTCOMES

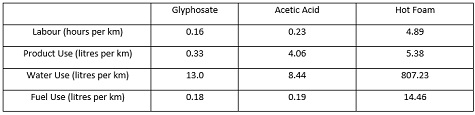

Some other interesting measurements drawn from this study are shown in the table that I have constructed below based on the data produced:

This study though looked much more closely at costs and carbon emissions. Again, the conventional approach of glyphosate use proved the most effective and economic. However it is in the area of carbon foot printing that approaches utilising glyphosate come out very well. Because they use less water and external energy in application, this mean their carbon footprint is much less. In fact the figures extracted from the report, based upon full life cycle analysis of the environmental impacts of the various approaches, indicate this strongly with, based on these figures and in these particular trials, one method estimated to be producing 6700 times more carbon emission for a given area of work than glyphosate. Given the council commitment to zero carbon, this is a powerful argument for retention of glyphosate in weed management programmes but again within a planned integrated approach.

It is important to re-emphasise that all situations vary but it does show that a simplistic approach to weed control is not possible. Whatever approach is taken requires a proper balancing of what level of control is needed, its location and type and a full co-ordination of approaches and methods. In their conclusions, the external consultants stated that ‘’to deliver sustainable weed management over large areas it is essential that control methods are examined scientifically to determine how well they work (efficacy) and how large their environmental and economic impacts are i.e., using an Integrated Weed Management (IWM) approach to testing. This scientific approach followed in the current experiment enables us to find out what works under ‘real world’ conditions and then make evidence-based decisions on how we want to manage weeds’’.

CONCLUSION

What is clear from both of these examples is that achieving the most sustainable approach in a given situation is not a linear decision but an integrated one. Everyone operating in the sector is committed to the objective of sustainable practice and that requires proper planning and agreement on the right integrated approaches to given situations. There is no universally applicable blueprint but it does require the use of professional trained managers and operatives operating to national standards, ideally meeting the requirements of the UK Amenity Standard overseen by the Amenity Forum.

‘Good decisions come from experience. Experience comes from making both good and bad decisions.’

Previous articles in this series

AN EXAMPLE OF SUSTAINABILITY IN MACHINERY SUPPLY

SUSTAINABILITY IN THE GOLF SECTOR

SUSTAINABLE PRACTICE IN THE AMENITY SUPPLY SECTOR